by Matt Dovey

Ursula lifted her snout to look at the mountain. The meadowed foothills she stood in were dotted with poppy and primrose and cranesbill and cowslip, an explosion of color and scent in the late spring sun, the long grass tickling her paws and her hind legs; above that the forested slopes, birch and rowan and willow and alder rising into needle-pines and gray firs; above that the snowline, ice and rock and brutal winds.

And above that, at the top, God; and with God, the answer Ursula had traveled so far for: what kind of bear am I meant to be?

She shouldered her bonesack and walked on.

* * *

There was a shuffling sound among the bracken, small but definite. Ursula hesitated, a dry branch held in her paws, her campfire half-built. Ambush wasn’t unheard of—so many bears sought God on the mountain that bonethieves couldn’t resist the chances to steal—but it had not been so large a sound, and she couldn’t smell another bear beneath the pine scent. It was something smaller, lurking in the dim light of the forest floor, behind the massive rough-barked firs that filled the slope.

“Hello?” she ventured, still holding motionless. “It’s quite all right. I’m building a fire, if you’d like to join me.”

A badger stepped out from the ferns, his snout twitching and cautious, a stout stick held warily in his paws. He eyed Ursula for a moment, weighing up the situation, and she gestured ever so gently to the fire she was building, trying to come across as safe, as friendly. As likeable.

He straightened and walked forward. He kept the stick before him, but Ursula understood. Bears could be dangerous.

Two more badgers followed him, one much smaller—”Oh, you’re a family!” said Ursula. “I’ll make a seat for you!”

She stood, turned, dashed back, dropping to four paws in her enthusiasm. She ran to where she’d seen a fallen log not twenty yards away by the river and hauled it back, her claws dug into its softened bark, dragging it and dropping it by the fire pit with a thud. She grinned at the family, proud of her resourcefulness—

The badgers cowered, the two behind the father with the stick, who tried to meet her eyes but couldn’t help glancing away for places to burrow and hide.

Ursula lowered herself slowly to sit. She made a point of picking up smaller twigs to lay on the fire, the least threatening pieces she could find. “Sorry,” she said quietly. “I forget how I can come across. Please. Sit down.” She concentrated on building the fire, determinedly not looking at the badgers, not wanting to startle them, trying not to let their fear hurt her nor to berate herself for getting carried away and upsetting others. For letting her shyness get to her: for overcompensating for it.

If only she knew who she was, instead of pretending so poorly.

“Thank you,” said Father Badger from the log, and Ursula smiled at him, keeping her teeth covered. “Forgive us our caution. We… have never met a bear before.”

“I’m Ursula,” she said.

“My name is Patrick,” said Father Badger, “and this is my husband, Willem, and our new daughter Ann.”

“And how old are you, Ann?” Another careful smile, friendly not fearsome, benevolent not bearlike.

Ann shuffled a little and squirmed in closer to Willem, who put an arm around her.

“She is a little shy,” said Willem. “We only met her an hour ago.”

“She’s why we came up the mountain,” said Patrick, smiling at his daughter. “Willem and I came to ask God for a blessing, and we found Ann burrowed alone beneath a root.”

“God showed you to her?” said Ursula eagerly, forgetting her calm façade in her excitement. “Is she near?”

“We never saw God,” said Willem, “and now we have no need. God has delivered us our gift already.”

“Oh,” said Ursula. “I mean, I’m happy for you! I really am. I just…”

“You hoped she would be near?” finished Willem.

Ursula shrugged, not trusting herself to speak. She put the last branch on the fire and hooked a claw around the strap of her bonesack, bones rattling inside the plain leather.

She felt, rather than saw, the badgers tense.

“You’re a bonethief,” said Patrick, voice flat and accusatory.

“We were warned of your kind on the mountainside,” said Willem, pulling Ann in close.

“They’re not my kind,” said Ursula carefully. “I don’t do what they do.”

“You carry the bones,” said Patrick. His paw lay on the stout stick, though if she truly were a bonethief it’d do him no use. She admired him that bravery, that certainty in his actions.

“Not all bears that carry bones are bonethieves,” said Ursula. “There is so much more that can be done. Please. Let me show you.”

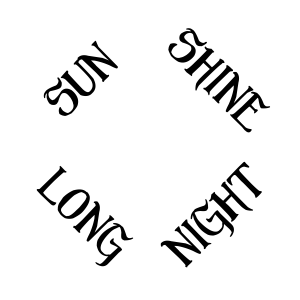

She reached into the bag and started pulling bones out, laying them on the floor, runes up. She spoke as she did, her voice low and even, trying to defuse the situation she had accidentally escalated again. “Every bone is from a family member. They’ve all passed down to me, bit by bit. This one here was Aunt Maud’s, this one Uncle Arthur’s, that there is my Great-Grandma’s right arm. Every bear carries four runes on their body—well, usually, by the end… anyway—four runes carved into their bones. One is carved on the left thigh bone at birth by one parent, another on the right thigh by the other when they consider their child has come of age.”

“How?” asked Willem, still cautious, but curious too.

“Bear claws are sharp,” Ursula said. “I would show you with mine, but I don’t want to scare Ann.” She tried a smile again, only a small one, tentative, but Ann responded in kind. “My parents cut through my flesh to carve their chosen rune on my bones. Their words hold me up everywhere I go, even this far from them. My father gave me HOME at birth and my mother gave me WATER. It helps me miss them less, as if they’re with me wherever I am.”

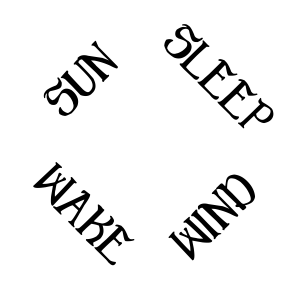

The bones were all laid out now, and Ursula began to choose from them. SUN, from Great-Great-Uncle Morris. WIND to cross it: Grandma Oak’s breastbone.

“The third,” she continued, “is given to us by God, shaped on our breastbone from the very moment of our conception. None of us ever know our breastbone rune. It’s only known when we pass our bones to our family.” She began to lay the bones before the fire pit. SLEEP, the next.

“And the fourth?” asked Patrick.

Ursula paused. She kept her voice flat when she answered, trying not to let any emotion into her answer. “The fourth we carve ourselves, on our right arm.” She chose WAKE from the pile, and put it in place:

A hot gust of air blew towards the campfire and it flared into life, awakening to a satisfying crackle. A gentle, sleepy warmth washed over Ursula, and she smiled to herself in satisfaction, then began putting bones back into the sack.

“I’m a bone poet,” she said. “The bonethieves only ever work towards violence and supremacy. All the bones they steal are only to help them steal more bones. They never think of all the better ways bones can be used.”

“How do you know what to choose?” asked Ann. Willem looked down at her in surprise.

“Well, the contraries must share something to bind the square together but have a tension that will give it power, and the neighbors should resonate in sound or form to amplify it, and the whole has to work to the purpose. I suppose I know what to choose because I know my bones well, what I’ve inherited and what might work.”

“No,” said Ann. “How do you choose what you carve on your own arm?”

“Oh.” Ursula picked a branch up, nudged at the fire with it, re-arranged the piled sticks to get them burning better. She mostly only knocked it over. “That’s… that’s what I want to ask God about.”

“Why?”

Ursula stared into the fire. How to express it? How to encapsulate the paralysis of choice, the fear of choosing wrong, the strange position of not knowing yourself?

“There is power in four,” she said, still staring. “Four bones combine into a poem of purpose. All of them interact and reinforce each other. I have to choose my own fourth rune carefully so that my purpose as a bear is strong. But how can I choose the fourth when only God knows what my third is?”

“So you go to ask,” said Willem.

Ursula nodded, feeling small, shrunken by her uncertainty, so unbearlike. “Choosing your own rune is… is the act of choosing who you want to be. It’s the moment of knowing yourself and defining yourself. Of finding your place in the world. But I don’t know who I am yet. Other bears just seem to know, but me… I try to be what I think other people need me to be, but it feels like everyone wants me to be something different, and every time I think I know which rune I should choose something changes my mind.”

“It is admirable that you worry so much about others,” said Willem. “Perhaps you should worry more about yourself, though. It sounds like this should be about you, not about the world.”

She prodded at the fire again. It felt—strange, to vocalize what had been churning and building in her head for so long. Stranger yet to be telling it to a badger cub. She looked up to smile at Ann, not a calming smile, but a real smile, a vulnerable smile, a—

Patrick had raised his stick, and was looking past Ursula. She turned, frowning, staring into the gloom of dusk that swam through the trees. There wasn’t—no, a glint—eyes reflecting flame—then a snarl, and Ursula’s fur bristled in alarm, and a sudden gust of icy wind extinguished the fire and knocked the badgers backwards.

Bone magic.

Bonethief.

“Run!” shouted Ursula to the badgers. She scooped up her bonesack and went to run too, but Ann was so small, and ran so slowly, too slowly, and Ursula realized the badgers would never escape.

She dropped her bonesack and began digging through it for bones. She only had to slow the bonethief enough for Patrick and Willem to get Ann underground, then she could run too. She couldn’t risk her bones. The bonethief ran forward on all fours, bones held in his jaws: he was a huge grizzly, bigger than Ursula, his fur matted with green-brown moss and sticky sap.

He pulled up at the sight of her bonesack—not in fear, she didn’t think, but in avarice.

“So,” he growled, low and fearsome, “you’ve been thieving round here for some time.”

Ursula drew herself up tall, her fur raised, trying to make herself seem confident and sure. “I have not. I’m no bonethief.”

“Quite the sack of bones you’ve got there for a bear traveling alone. Or are those little badgers your companions, and not just a snack you’re luring in?”

Ursula risked a glance back at them—Ann had stopped to watch, and was refusing to be pulled away—and it hurt her to worry they might believe him for even a moment. Surely they already knew her better! But she had to seem strong and bearlike now: she couldn’t show any concern for smaller creatures in front of this other bear.

She lifted her snout. “My family has entrusted them to me and my skill. I am a bone poet.” She said this with as much pride as she could in the hopes it would impress the bonethief, forge a connection between them and allow her to talk herself out of this without any conflict.

But it did not. He laughed, a deep roar, a bellow of mirth that shook needles loose from the pines. “A poet? What fresh scat is this?”

His mockery stung, but not just because she’d failed to impress him. No, it stung because she was proud to be a bone poet, she realized. She was proud of the things she could do. She was proud of the connections she could make between bones.

She was proud of the way Ann had looked at her as she explained. She was better than this thief.

“I’m more deserving of these bones than you’ll ever be.” Her voice now was angry, not by choice, not to elicit a response from him, but because she meant it.

The thief grinned back at her, exposing his fangs. “Doesn’t matter if you deserve them. Only matters if you’re strong enough to keep them from me.” His paws moved to his bones, and he began laying out his square.

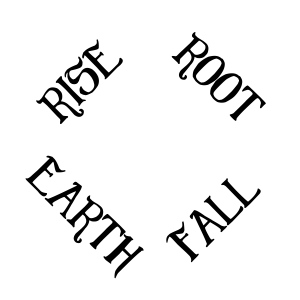

Not enough time to think, only to react. Ursula grabbed bones from her sack almost without thought, going by touch and instinct, and laid them out in a square:

The soil beneath the bonethief fell away like melting snow and the exposed tree roots started to twist and writhe, a tangle of wood squirming with life. The bear stumbled and fell into the trap, snarling, swiping at the roots as his back legs sunk into the soft ground.

Willem was scrabbling at the earth, burrowing, as Patrick stood before Ann with his stick held out. It’d do no more than scratch the throat of the bonethief as he swallowed. His bravery brought her heart to her throat.

The bonethief roared. “Stupid sow! I’ll take all your bones! I’ll rip yours from your flesh!” He grasped at the roots, hauling himself out of the loose mud.

Ursula rifled through her bones again. She had to do something else to slow him down, so she could—

No. She had to do something to stop him. If he didn’t get her bones, he’d chase someone else’s. He’d eat other small mammals he came across, hurt other travelers. But she was a bone poet, and she could outthink him. She could stop him here.

The bonethief was free of the earth now, arranging his small clutch of stolen bones to send another blast of icy wind; she could see the runes from here, WIND and WILD and STRONG and ICE. She chose her bones with more care, though no less speed:

Her square burst with light, and even knowing it was coming it was all Ursula could do to shield her eyes, positioning herself to protect the badgers. The bonethief was less prepared—staring greedily at Ursula, at her bonesack—and the full flash of light blinded him. He yelped in agony, in surprise, as the sight was burned from his eyes. If she had done enough he would no longer be able to read the runes on bones. She doubted he could recognize them by touch.

But he, too, had finished his square: and he was closer to her this time, and the blast of wind gusted hard. With her paws raised to shield her eyes from her own blast, Ursula was unbalanced, and she was knocked backwards, down the slope, all her bones scattering in the chill wind, and she rolled and fell towards the river and into the river and knocked her head and—

* * *

Icy water splashed at Ursula’s snout. Slapped at it, even. She stirred, groggily, and opened her eyes to a salmon flopping on her face. She swiped at it unthinkingly, knocking it away, then groaned as she realized how hungry she was.

With an effort, she hauled herself from the river and shook the water from her fur. In the dim light of dusk it was difficult to tell how exactly far she had fallen down the mountain, but the ground around her sloped only gently, covered in tall grass and meadow flowers closed for the night.

She was as far from God as she had ever been, and she no longer had her bones. She no longer had her friends—oh, she hoped Patrick and Willem and Ann had gotten away! Surely they were small enough and quick enough to avoid a blinded bear?—and she was not sure she had hope, either. It had taken days to ascend the mountain before, when she had her bones to intuit the way and catch leaping salmon and all the other little helps her poems gave her. Could she do it again now? What if another bonethief found her? Even without her bonesack to steal, she could be killed for her own bones.

But what else? Go home, and never know who she was? Never know who she should be? Could be?

Ursula pulled herself to her paws, cold muscles rasping, and dragged herself up the slope.

Walking on all fours in her exhaustion, her head bowed, the sun long set, Ursula trudged through the forest, stumbling wearily into alders and birches, knocking some over with a creaking, snapping shock of sound, loud in the silence of the night, stirring birds from their sleep in a panic. She fell into an atavistic trance: cold, hungry, determined, focused only on the ascent, forgetting even why she climbed, lost wholly in her drive to get higher, higher, higher.

So it was that she became aware of the light only slowly.

The color of it was the first thing she noticed. It was too blue for dawn. As she lifted her head to look closer, she saw the strangeness of the shadows—flickering, oddly angled, moving with each tired step like a broken branch swaying in the wind.

And she looked up at last, and saw a sleek black bear walking beside her, smaller, lither, and glowing gently.

“Hello Ursula,” said God. “Would you like something to eat?” God gestured towards a clearing, where three salmon hung by a small, crackling fire that could not have been there a moment before. Had the clearing even been there?

Ursula lumbered forward and fell onto her haunches by the fire, snatching one of the salmon with a swipe and chewing it in silence, still lost in her animal exhaustion. God busied herself with the trees as Ursula ate, shaping branches with a touch and humming softly as she did, new leaves sprouting where her claws danced.

“Have I—” said Ursula, once she had eaten, warmed, returned to herself—”have I walked so long I am at the top?” She looked about at the trees, but they were still broad-leafed, of the low slopes.

God smiled up at a rowan; she reinvigorated one final branch with an upwards stroke, stretching on her hind legs, then sat down before Ursula. She exuded—contentment.

“No,” she said, her voice high and clear like birdsong at dawn. “I am rarely at the top. It’s so desolate up there, beautiful as it is. The point of the mountain is only to see how determined pilgrims are. Patrick and Willem could never have ascended above the snowline, but they climbed so far on such small legs. If they had that devotion in them, if they were so driven by love, then Ann could do no better than their care.”

Ursula’s throat tightened in fear for the badgers. “Did they—are they—”

“Yes,” said God, “they are fine. You did enough. Thank you.”

Tension flooded out of Ursula like meltwater. The thought had weighed heavy, but—but they were well. She hoped they would be happy together.

“I believe, by the way,” said God, “that these are yours.” She reached behind where she was sat—where there had been nothing but grass and fallen twigs a moment before—and produced Ursula’s bonesack, clearly full.

Ursula lurched forward with a gasp, snatching the bag quite before she could comprehend the rudeness of what she had done, and to whom she had done it.

“There are,” said God, “a few more bones in there than before. You will be a better keeper for them, I think.”

Ursula’s breath caught in a sudden clench of nervousness, and she lowered the bag. So long spent climbing the slope, anticipating this moment, and now she couldn’t get her words in order. There was so much to say, such an entwined web of emotion and expectation and duty and hope and thought and fear that she couldn’t possibly order it anymore, couldn’t untangle it to find the starting thread, couldn’t do more than hold the whole concept of what she needed in her head at once, complete and connected and indivisible.

But she had come all this way, and perhaps if she just started. “About bones—”

“I know,” said God. “Of course I know.” And she smiled again, and stood up and walked over and hugged Ursula tight. Her glow expanded to surround them both, and the contentment too.

She spoke in Ursula’s ear. “The rune on your breastbone doesn’t matter. You can complete your own poem without knowing. You don’t need to know who you are to choose who you want to be. You don’t need to let other people’s choices in your past define your future. It doesn’t matter what I wrote when I made you in the swirling potential of the Before, when the path to your existence and that rune was laid in the What Nexts—it only matters what you feel now.”

“But I need to finish the poem of my bones! If I don’t choose the right rune to complete the four, to complement the three I’ve got, my purpose won’t be as strong as it could be!”

“Ursula, you are not a poem, you are a bear,” God admonished. “You do not have to be a purpose—you are the purpose. You are who you are, not what you can offer.”

God released Ursula, held her shoulders in her paws, smiled at her through brimming tears and a face filled with pride. “The words you have on your bones already were only meant to get you this far, when you could decide for yourself whom you wanted to be.”

Ursula choked back a sob, but the dam burst anyway, and she cried into God’s shoulder. With relief, with possibility. With acceptance.

God held her there a long while, as the sun rose and the earth warmed and the flowers opened to the sky.

“What do you think you will choose, then?” asked God. “I will help carve it, as an honor to you, and as thanks for saving the badgers.”

Ursula looked at her bonesack, and thought of all the poems waiting in there, all the combinations and implications and things that could be. And now, with the new bones, there were so many more possibilities, so much still to see and learn. So much still unknown.

“I don’t know,” said Ursula. “I don’t know at all, yet.”

And for the first time, that answer gave her contentment.

* * *

Originally published in Sword and Sonnet.

About the Author

About the Author

Matt Dovey is very tall, very English, and most likely drinking a cup of tea right now. He has a scar on his arm where his parents carved a rune into his humerus: apparently it was BISCUIT, and yes he would like another digestive, thank you for asking. He now lives in a quiet market town in rural England with his wife and three children, and still struggles to express his delight in this wonderful arrangement.

His surname rhymes with “Dopey” but any other similarities to the dwarf are purely coincidental. He has fiction out and forthcoming all over the place; you can keep up with it at mattdovey.com, or find him time-wasting on Twitter as @mattdoveywriter.