by Mary Jo Rabe

Fred the Opossum laid his moderately chubby and maximally furry body down onto the dry, brown grass next to the noisy duck pond and diffidently dipped his claws into the murky, cold water. Some of the crunchy insect parts that he had had for dessert the day before floated away; most didn’t.

Fred should have cared or at least sloshed his paws in the water to clean them. It was to his obvious advantage to keep his grasping appendages free of obstruction. Plus, Fred usually liked to feel clean.

The mud at the bottom of the pond helped soothe sore paws. An opossum that tended to his body parts tended to live longer, which had been Fred’s major goal in life. Lately, though, he wondered what a longer life was good for.

The elderly ducks swimming close to the shore looked up but didn’t bother to quack. They correctly sensed no danger from Fred’s lethargic presence.

Even though he didn’t really feel like doing anything, Fred emptied his mind and tried to soak up some impressions from the microbes in the pond.

The microbes were only one-celled creatures individually. But when they joined together in their group mind, they were far superior in brainpower to all other creatures Fred had ever encountered. Their telepathic powers were incredible.

Fred was grateful to the microbes for even paying any attention to him. His thoughts must seem unbearably primitive in comparison.

However, he had to concentrate strenuously if he wanted to understand what the microbes communicated. Talking to the microbes often exhausted him. Their messages resulted slowly. Sometimes they were interrupted for long periods of time.

Fred had the necessary patience for such communication. However, as he got older, he did notice that he sometimes no longer had the physical vigor he needed for listening. Still, he enjoyed hearing from the microbes.

Other opossums with whom Fred had had sporadic contact in the past ridiculed him for talking to microbes. Fred no longer bothered to explain that he listened more than he talked. If other opossums didn’t want to access available information, he couldn’t force them. In addition, he had less and less desire to cajole impatient fools.

“What’s wrong?” the group mind of the microbes in the pond asked. “You seem a little despondent.”

“I honestly don’t know,” Fred said. “Maybe I’m getting old. Everything just seems so pointless, the same routine day after day.”

“Well,” the microbe group mind said. “We don’t really understand this aging thing you multi-celled creatures go through. Our minds exist together in the group and don’t degrade when we switch from one decaying, old, cellular creature to a brand new one.”

“Yeah,” Fred said. “Then you never have regrets?”

“Regrets?” the microbes asked. “We often evaluate our actions and ask ourselves if we chose the most effective method for what we hoped to accomplish. Sometimes we are satisfied with results, sometimes not. That’s when we brainstorm about possible different strategies for future events. Aren’t you satisfied with your results? It was only last month that we and dark energy helped you save the universe from being assimilated by a parallel universe and destroyed in the process.”

“That’s true,” Fred admitted. “That should have made me stay happy longer. I guess I have started reflecting on the fact that I am getting older and wish I had done some things differently in the past,” Fred said.

“Why not just do them differently in the future?” the microbe group mind asked. “That’s what we do.”

“The same situation is unlikely to happen again,” Fred said sadly. “A few years ago, out of purely selfish motives, I insulted a female opossum and drove her away from the farm. I didn’t want to share anything with her, not my turf nor the food from the humans in the farmhouse.”

“That is a logical decision, obviously beneficial for your own survival,” the microbes said. “Why do you regret it?”

“It was unnecessary,” Fred said. “The humans have shown themselves to be willing to feed any number of animals who show up at the door. Sometimes there are twenty or more cats who patrol the farms in this region, always on the prowl for better food. One more opossum wouldn’t have meant that I got less food. The farm is also spacious enough for any number of my species. And now I wish I had more opossum company, creatures on my wavelength, creatures no smarter than I am.”

“Then behave differently the next time an opossum wants to stay on the farm,” the microbes suggested

“There haven’t been many since she left,” Fred admitted. “She may have bad-mouthed me to others.”

“Well,” the microbe group mind said. “Then you want to change your actions in the past.”

“Right,” Fred said. “Unfortunately, that is impossible.”

“Maybe, maybe not,” the microbes said. “We’ve never thought about that before. Give us some time to brainstorm.” And their telepathic messages stopped.

Fred was always glad to do anything the microbes requested. Despite the huge difference in brain capacity, theirs being infinitely greater than his, they were his best friends.

Fred thought he’d stay at the pond for a while. It was pleasant enough here. It smelled like the hogs hadn’t been near the pond for some time now. Fred’s pink nose on his long, thin snout couldn’t detect even a whiff of hog excrement, just overly ripened corn from the fields.

Fred liked the pond. It was one of the reasons he decided to make his home on this farm. One of the previous farmers had dug the hole that became the pond thinking that it would be used by the farm animals. As far as Fred could determine, that didn’t happen all that often.

The pond was more or less hidden behind the three-story wooden barn, a shabby structure with weathered planks. Earlier, more prosperous farmers had probably painted it red. Some of the wooden slabs still had traces of that paint, though many of them were now missing. The current humans didn’t seem to be concerned with appearances.

Fred had always been impressed by the structure. It was significantly larger than the machine shed or the farmhouse. These human creatures might be clueless about many things, but they did construct striking buildings.

The sunlight was getting dimmer, and so Fred started thinking about supper. There were no clouds, and so it might not rain, which didn’t matter. His thick, gray fur protected him from hypothermia, and he quite enjoyed gyrating briskly to get the thick raindrops off his bristly hairs.

There would probably be some new, semi-feral farm cats blocking the door to the farmhouse. It was tiresome, always having to assert his opossum’s privilege and chase the cats away. He had nothing against the cats. They were free to eat as much as they wanted, but only after Fred was finished.

However, it was a nuisance having to re-establish the pecking order every time a new cat appeared. New cats had to be shown that Fred was in charge of all non-resident mammals on the farm.

While the cats did on occasion catch and kill aged or slow rodents, they never bothered to eat them. Instead, they lined up for the delicacies from the farmhouse. The humans who fed animals at the door were kind-hearted despite being generally incomprehensible.

The food they offered the visiting animals was excellent. He never was sure when exactly they would offer it to the outside guests each day, but Fred was flexible. He knew the food prepared by humans was worth waiting for. It was just as tasty in its own way as the carrion and insects that Fred munched on between meals.

Fred appreciated the humans in the farmhouse but had no desire to spend time with them. It was common knowledge, or perhaps inherited memories among opossums, that some humans consumed opossums, calling them tasty vittles. He didn’t have the feeling that the humans in this farmhouse wanted to eat him, but caution was a useful virtue.

So Fred scampered around the barn and down the hill to the two-story, old-fashioned farmhouse. At one time, it had probably been painted white, but now there were more gray boards than white.

His timing was correct. Just as he got to the farmhouse, the screen door opened and a tall, female human, followed by her child, brought out bowls of meat and milk and water. Again, the child seemed to understand that Fred was saying “hello.”

When the adult headed back into the house, Fred jumped up the steps to the door. Fred growled as he shoved his way through the crowd of cats, who, fortunately for them, quickly made way for him.

“Fred’s here,” the child shouted. Fred wasn’t afraid of the child. Fred, as a matter of fact, did have his own, genuine opossum name, but after the child had started calling him “Fred” a few years ago, Fred decided to claim it for himself. Now he associated the name “Fred” with pleasant memories of the food the humans provided.

The food made Fred feel energetic for the first time today. Although he had no real hope that the microbes could help him remedy his past mistake, he decided to return to the duck pond and ask. He thought he could see tiny waves on the surface of the pond water.

“Hey microbes,” Fred began his telepathic message. “Were you able to come up with anything?”

“Indirectly, perhaps,” the microbe group mind said. “There’s nothing we can do; we are just microbes, after all. However, we were able to send messages up and down the chain of structures in the universe, and dark energy has agreed to help you. It is grateful to you for informing it about the previous danger to the universe.”

“Help me how?” Fred asked. He didn’t want to indulge in too much wishful thinking. That only depressed him.

“You can’t travel into the past,” the microbe group mind transmitted patiently. “But we can send your brain waves out to the dark energy that is expanding the universe, and it can jump the thoughts back, though not very far. When exactly was this mistake you wish you hadn’t made?”

“Three years ago,” Fred said. “I still don’t understand. My thoughts go back in time, but I don’t?”

“Right,” the microbes said, this time not quite as patiently. “With the power of our group mind and dark energy, your thoughts can enter the mind of your previous self and perhaps influence him. There aren’t any guarantees, of course. If you recall, you were quite stubborn back then.”

“But will I know how much my thoughts today influence the actions of my previous self?” Fred asked.

“We’re not sure,” the microbes said. “Try to understand the situation. Depending on what effect your current thoughts have on your previous self, you may experience changes in the here and now, changes brought about by influencing your previous self. However, dark energy will prevent your possible actions from reversing the changes it made in the universe. Dark energy prefers the universe as it currently exists.”

“Fine with me,” Fred said. “Can anything go wrong?”

“Nothing can go wrong with the process,” the microbes said. “We and dark energy have investigated all eventualities. You just may not be happy with all the results, though, if there are changes you have to deal with due to new actions of your previous self. You could find yourself blacking out occasionally when your new memories conflict with the memories you have stored as of now.”

“But can I control the thoughts you send back?” Fred asked. “They aren’t that complicated. I just want to apologize to the female opossum and tell her I would be happy to share this farm with her.”

“Got that,” the microbes said. “We’ll send your brainwaves on to dark energy to be transmitted back to Fred the Opossum on this farm three years ago.”

* * *

Fred felt like he had passed out briefly, but then he felt like he was floating. He saw his previous self in the cornfield, munching some insects contentedly. My goodness, he had looked good back then; he never realized how good. He was slim and yet muscular with a thick, shiny fur.

Not sure exactly how to proceed, Fred, or rather his thoughts, floated above his previous self as previous self got up and scampered over to the farmhouse. When his previous self climbed up the porch stairs, he saw that the female opossum was already there.

The door opened, and the child yelled, “Fred’s there, and so is his girlfriend. I’m going to call her ‘Frieda’.”

Fred felt the jealous anger in his previous self’s mind. That was the reason he had driven the female opossum away. He had been jealous of the attention she got from the humans and that was why he hadn’t wanted to share anything with her. His previous self was putting a few choice words together to chase the female away.

“No,” he thought, hoping his thoughts would enter his previous self’s brain. “Be kind to the female. Make her feel at home. You have nothing to lose and everything to gain.”

His previous self shook its head violently, and so Fred hoped that meant the message had gotten through.

“Trust me,” Fred thought. “You know the value of kindness. Kindness creates more kindness. Think of the future, the world you want to live in. Get out of your own way and be kind to another opossum.”

His previous self seemed to inhale deeply. Then it barked softly to the female, “You are welcome here, both with the humans and on the whole farm. I know it’s frightening at first, but I’ve been here for over a year now, and I can recommend this location as a home. And, in my opinion, the young human gave you a pretty name. I like ‘Frieda’.”

The female looked skeptical but didn’t run away. Fred’s previous self then motioned for her to eat out of the meat bowl with him. When they finished, the previous Fred told the female she might like to follow him to the cornfields where they could find some tasty insects as dessert.

The two of them turned and left the farmhouse, at which point twenty feral cats stormed the porch and ate everything that was still there.

Fred was relieved. He really owed the microbes and dark energy for this favor.

* * *

Fred shook his head. “I must have passed out,” he called to the microbes. “Did it work?”

“Yes, of course,” the group mind answered. “We wouldn’t have suggested it if we didn’t calculate at least a fifty-one percent chance of success. Dark energy says you persuaded your previous self to be kind to the female opossum instead of scaring her away.”

“Thank you,” Fred said. “I never realized what a burden this memory was to me. Now I feel truly at peace with myself.”

“Naturally,” the microbes continued. “There have been a few changes in your life due to this change in behavior.”

“Huh?” Fred asked. “The changes have to be good, though, right?”

“The results are interesting, and not inopportune,” the microbe group mind transmitted. “It might be easier for you to discover them for yourself instead of asking us questions, though. We can’t always determine what is important to you because we have more pragmatic standards than you emotional creatures with no group mind to mediate your feelings do.”

“Okay,” Fred said. “What do I need to do?”

“Waddle down to the end of the lane and check out the new sign,” the microbes said.

That seemed to be odd advice. Fred, however, had taught himself to read human language long ago. He marched down the lane, well maybe not as fast as he once did. Underneath the mailbox was indeed a huge sign that said “Opossum Preserve. No Hunting!”

“That had to be good,” Fred thought. He had never had any trouble evading the clumsy hunters on the farm before, but it was good to know that they were no longer a threat.

He strolled back to the farmhouse. Strange, there weren’t any cats prowling around, but they were probably out checking out the food at other farms. Cats always suspected there was better food somewhere else. They were wrong, but cats never listened to Fred.

Suddenly a mob of young opossums dashed out of the cornfields and stood in front of him. “Are you all right, Dad?” one of them asked. “Mom was worried because you were so absent-minded after supper.”

“Yeah,” another one said. “Mom hoped we could find you in the cornfields or back at the duck pond. That’s where you always go to rest your mind.”

“You promised to show us your old hunting grounds in the woods,” another said. “You claimed we could find the best-tasting amphibians there.”

Fred tried to make some sense out of this unexpected turn of events. Obviously, he and Frieda had gotten on well, but now what? Fred had previously never considered giving up his solitary lifestyle, but apparently, he had changed his mind during the past three years.

“Uh,” he said. “I want to go to the duck pond first and clean off my claws. Wait for me at the farmhouse, and then we’ll go.”

The young opossums cheered and ran off. Fred charged up the hill to the barn and back down a different hill to the duck pond.

“What the,” he began.

“Yes,” the microbes said. “You and Frieda are quite a prolific pair of opossums. Every year there are at least ten new little opossums here on the farm. The humans noticed this a year ago and were able to get recognition and funding for making this farm an opossum preserve, where opossums can live safely and where researchers show up now and then to see what they can learn. This saved the farm from being sold.”

“Okay,” Fred said. “But what about me?”

“You have turned into an extroverted, happy father of many, many children,” the microbes said. “Apparently this was something you always wanted but never admitted to yourself.”

“But I don’t remember anything after Frieda and I walked to the cornfield,” Fred said.

“And you won’t,” the microbes agreed. “But you can create new memories, and Frieda can fill you in on what you don’t remember. She is used to your memory lapses. She thinks it is part of your personality.”

“I don’t know,” Fred said.

“We calculate that this will continue to go well,” the microbe group mind said. “Besides, you can always ask us for advice.”

“Then, thanks, I guess,” Fred said. “It’s all just a little much for me right now. But maybe you’re right. Maybe this is the kind of life I was yearning for.”

He turned around and walked back to the farmhouse where some thirty opossums were waiting for him. He didn’t want to disappoint them.

Still, he had one question. “Do any of you know what happened to all the cats?” Fred asked the group.

“Don’t you remember?” one opossum said. “Mom told them to leave the farm. She didn’t want any competition for food.”

Well, Fred could live with that. Now he had to find a way to learn all his kids’ names.

* * *

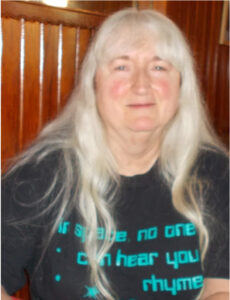

About the Author

About the Author

Mary Jo Rabe grew up on a farm in eastern Iowa, got degrees from Michigan State University (German and math) and University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee (library science). She worked in the library of the chancery office of the Archdiocese of Freiburg, Germany for 41 years, and lives with her husband in Titisee-Neustadt, Germany. She has published “Blue Sunset,” inspired by Spoon River Anthology and The Martian Chronicles, electronically and has had stories published in Fiction River, Pulphouse, Penumbric Speculative Fiction, Alien Dimensions, 4 Star Stories, Fabula Argentea, Crunchy with Chocolate, The Lorelei Signal, The Lost Librarian’s Grave, Draw Down the Moon, Dark Horses, Wyldblood Magazine, and other magazines and anthologies. You can find her blog at: https://maryjorabe.wordpress.com/