by Frances Pauli

The streets of men fall silent long before Charlie slinks from his master’s side. There is no movement in the house for days, not even when he cries or pees the carpet. No more breath lifts the man’s body, no life remains, and Charlie’s loyalty falters as his belly empties.

As the body begins to smell like meat.

He tears the screen from the bedroom window, squeezes out, and runs with silver strings trailing from his claws. The pattering echoes as he goes. No other sound competes with Charlie’s flight. No one shouts or whistles. Not a single car horn blares anger when he crosses the wide street and lopes past silent storefronts.

He scents as he runs, nose skipping along the pavement like a stone on water. His ears swivel to either side, twisting and alert for any sound, for anything at all. He finds the first bodies after only another block. He smells them long before buzzing flies sound the alarm.

The people lay where they have fallen, twisted and with their hands open as if clutching something that isn’t there. Their eyes are wide and staring so that Charlie cannot help but growl. His throat rumbles at each dead stranger. The fur along his spine lifts and his heart beats, danger, danger.

He smells the flesh, sweet and overpowering, but there is a sharpness behind it. He cringes even while his tongue lolls. The man has not fed him for many days, will never feed him again. The people in the street all stare at the sky, and Charlie knows he is alone. He whines, lowers his tail to the earth and scoots far around the next, reaching corpse.

Now he clings to the buildings as he goes. The streets are choked with the dead, and Charlie rubs at his nose with one paw and shakes as if to dislodge the odor. He sits beside still glass and pants at his own reflection.

In the distance, a howl rises. His ears stand at attention. His tail thumps once before remembering to be afraid. His body cringes, belly tight to the ground, but he cannot stay away and slinks between the buildings with his ears tuned. Each time the sound comes, Charlie eases closer. He crosses streets, weaving between the dead. He follows alleys where the scent of garbage is a relief from the stench of decay. And more. The sharp odor troubles him. His nose flinches from it, insisting there is danger there.

Charlie finds the other dogs and wishes he hadn’t. He lingers at the alley’s mouth and watches them drift between the corpses. Their bodies are lean, showing angular bones beneath dull pelts. They had no master, have been alone much longer. Their hunger is enough to dare the smell. He sees it, in the curling of their lips and the dark stains growing over their teeth.

Danger.

He runs from them. Charlie darts from alley to alley, sticking to the familiar reek of cast-off human things and only entering the streets when the way ends and he must cross to the next slim sanctuary. He hears the dogs’ snarling long after he’s left them behind. He sees their dripping jaws even with his eyes closed.

He races, turns, loops back and realizes he is circling them. He is dog and they are pack. He is alone. He has nowhere else to go. His pads brush against asphalt. His nose twitches. The garbage is fresher here, but there is something else behind it. A scent that is neither death nor rot.

Charlie stops and lifts his nose high. His tail swishes, wagging joy at the new aroma. He follows it, a better chase than circling the starving pack, a more noble quarry, and one that doesn’t push his belly lower. The thread of something fresh and edible draws his feet between the buildings, up another alley to an open door in the rear of one storefront.

The smell lives here. Charlie slips inside without hesitation. His tail thumps against the door, wagging in anticipation. He creeps farther, following his nose while the smell sings to his belly. There are shelves inside, a maze of cans and boxes. There are glass doors along the walls, and in one corner, a bucket full of water.

Charlie drinks. His tongue uncurls and hangs soft again and happy. He finds bread on a low shelf, and whimpers before remembering there is no master. A pang of guilt still lowers his head as he steals the loaf. He still cringes as his teeth tear into the plastic, as he rips the bag with his claws and then eats both bread and garbage in his haste to be full again.

It is glorious. Soft and tasting of man’s things. Charlie eats two loaves before heaving. He devours his own sick, drinks again, and curls up between the shelves to sleep.

When he wakes, the cat is there. She sits atop the shelf, glaring. When Charlie barks, she turns away, shows him her butt, and flicks her tail dangerously over the edge. It is a dare he doesn’t take. Charlie remembers cats. He whines and puts his paws over his nose, but his tail thumps. He is not alone. Even if she is a cat.

She ignores him. He pretends not to watch her. She catches him and hides behind the counter to punish him. She has food there. Charlie can smell it, but he knows better than to expect a cat to share. He eats the bread, tears open a few bags of dry crunchy things, and waits for the cat to come back and glare at him some more.

They live together in the store for two days before he wakes up to purring. His belly vibrates with it. The cat sleeps curled up beside him, hind end to his face and long tail tickling his muzzle. When his tail thumps, she slaps it. Pin claws prickle the sensitive skin but Charlie loves it. No one has touched him since his master stopped moving. He holds still as a stone and lets her sleep in peace.

Charlie lays his head on his paws and dreams of the master. The cat is back on her counter when he wakes, but he can feel the difference. Even when she glares.

They eat together, the cat behind her counter and Charlie picking from the packages he can chew his way into. They haunt the shop by day, the cat sitting in the front window and Charlie guarding the back door. He fears the other dogs now. Now that he has something to protect. At night the cat sleeps by his side, alternately clawing his tail and grooming him with her rough tongue.

The water in the bucket is gone, but there has been rain. He only has to wander to the alley to drink. Eventually, the shelves will empty. Charlie imagines leaving with the cat, finding another store, a full bucket and more bread. He wanders to the end of the alley when the puddles dry up. He finds the first dead dog there, eyes staring at the sky, paws stiff and reaching.

Charlie growls at it. His tail drags. The sharp smell is in his nose again, and he whines and paws at his face. He shakes, steps around the corpse, and ventures into the streets for the first time since finding the cat.

All the strays are dead. They lay beside the remains of man, a gaunt, furry echo of the other death. There are birds as well, corpses of crows and rats. The sharp smell overpowers even the scent of rot, and Charlie backs from it, turns tail, and races back to the shop’s shelter.

He barks for the cat, calls the warning over and over. Danger. Danger, danger.

Charlie races between the aisles. He knocks over the boxes. He barks, whines, and doesn’t believe the cat is gone until he peeks behind the counter. A stalwart white hopper stands above the cat’s dish. The kibble is all gone. The dish is empty. He sniffs to be certain, sits, and howls to the ceiling.

He remembers cats do not need a pack.

Though he is certain she will not return, Charlie waits in the store for three more days. His tongue dries up. His belly tightens, complaining so loudly that he wakes with a start. The hunger aches again and, eventually, Charlie slips through the back door and returns to the streets.

This time he runs without dodging. He leaps the corpses and he lets their stink drive him onward, down the long avenues between the buildings, down and away from the things of man. He races until his pads bleed, until the buildings finally spread their numbers. Charlie limps past little houses then, stalled cars, and fenced yards where the bodies have been left inside, where the stink is only a whisper behind grass and metal and, in the distance, the clear bright smell of water.

He makes for that, leaving the road when it veers sharply in the wrong direction. The grass feels like heaven and memories. He longs to roll in it, but his tongue is dry and the tears in his feet feel like fire. Instead, he crosses at an angle to the wind, keeping the water in his nose until he tops a rise and can see the glinting of the pool ahead.

A house squats behind it. A high chain fence surrounds it.

Charlie digs, churning his own blood into the soil, until he can squeeze underneath. He drags to the pool and laps at green water. His belly shudders. His paws leave pink tracks around the patio. He sniffs and catches wild odors, trees and dirt and animals that never lived inside a house with man.

Animals that have never eaten the sharpness that means dying.

In the shade of the house, Charlie rests. He drinks and sleeps until he is strong enough to think of food again. He imagines the shelves of bread, sniffing at the door that won’t open. He reaches and finds the windows closed.

When night falls, he hears the howling. This time it sings away from streets and houses. It calls from the space between man’s cities, and there are many voices. Charlie’s tail wags. He squeezes under the fence, leaves the water, and trots toward the trees. The howling drifts into the fringes of man, singing to his heart and making his pain and hunger fade like smoke on a steady breeze.

He is dog and that is pack. He bounds and barks and hears a new voice from much closer.

“Here, boy!”

Charlie skids to a halt. His tail dances, frantic, in all directions. The howling comes, but now it sounds far away. Almost as soon as he hears it, the whistle follows.

“Here, boy. Come!”

His tail dances, but he lowers his head and whines. Across the grass, a man steps between the houses. Beyond the trees, the pack sings another chorus. Charlie writhes against the grass, barks and presses his belly to the cold earth.

The man eases nearer. He stops and lowers himself until their eyes can meet. Charlie’s nose catches a forgotten scent, meat that hasn’t begun to rot. His tongue loosens, lolling between his teeth. His tail thumps and the man reaches out, makes the meat an offering.

“Good boy.”

He sniffs it, brings his nose right up to the man’s fingers and finds the sharpness there. When he flinches away, the man lowers the offering, tilts his head and whistles faintly. He drops the meat and waddles backwards, taking the odor with him.

Charlie eats. The meat is dry and too salty, but he salivates at the first bite and wolfs the rest down as if it were fresh liver. Before he’s finished, the man is reaching again. His fingers curl more than they should. They smell of the sharpness, but Charlie leans into them just the same. When the man pats, the dog melts into him.

This is master. He is dog.

The man leads, and Charlie follows. They walk in the grassy space between the roads and the trees. The sun dips behind the city. A house waits at the edge of the wild. The door is open, and it smells of home inside, of life before the sharp scent ruined the world. When the man enters, Charlie’s paws move.

One step in that direction, one sniff, before he remembers doors are traps.

Charlie stalls outside that threshold. He barks, but when the man whistles, he presses his stomach to the ground and refuses to enter. The man squats inside the doorway. He sings the song of dogs and masters. He whistles, claps his hands, and brings more meat to the threshold.

They stare at one another until the man sits, dropping his head in his hands. Charlie rests his muzzle on his paws. He whines, thumps his tail. When the man throws him the meat, Charlie eats it. He longs for water, but the pool is in the past now, too. The moment, the threshold, and the man are everything.

In their stalemate, he hears the howling, far off.

Eventually, the man rises. He wanders deeper into the house and Charlie stands, tempted despite the closed windows and the door. He trembles. His ears flatten and lift and flatten again. Before he relents, the man returns. He pushes a chair through the doorway, drags the thing out of the house.

They sit together at the end. The master in his chair and Charlie at his side. When the man reaches, the dog leans in, savoring the contact but also noting the stiffness, the curling and tightening of fingers. He sees the way the man pauses every few breaths to stare at the sky, just as he hears the pack singing from the forest.

It won’t be long.

When the man is gone, Charlie will answer the howl. He’ll run, away from the streets of men, and live. Maybe he will see the cat again. She’ll glare from some high branch while his pack runs below. For now, Charlie remains. He sits beside the man. He waits while the sun sets. When the man stares at the sky, Charlie looks, too.

He hears the wind and the earth and the future while the man fades.

He is dog.

* * *

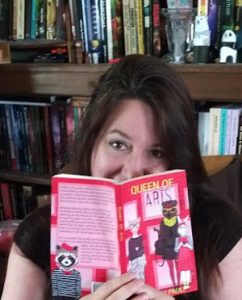

About the Author

Frances Pauli writes numerous novels and stories across the Speculative Fiction genres. She greatly prefers anthropomorphic characters, and you’ll likely find some kind of animal in just about all her fiction. She lives in Washington State with her family, a wide variety of pets, and far too many distracting hobbies.

Her fiction has won a Leo Award and been nominated for a Cóyotl Award.

For news and title updates, you can find her at www.francespauli.com.

This story was amazing. very well done indeed.