by Mary Jo Rabe

It turned out to be a perfect time for saving the universe. Fortunately, Fred the resident farm opossum was paying attention, as always.

After a long nap, some careful foraging activity, and resultant nibbling, Fred the opossum laid his moderately chubby body down on the brown grass and dipped the sticky claws on his front feet tentatively into the muddy duck pond.

The ducks flew off, quacking loudly in protest but acknowledging the potential danger of Fred’s presence. Completely unnecessary. Fred would never bother trying to kill a duck. Too much effort involved. Duck cadavers, marinated in the pond for a couple of days and covered with a crust of crunchy maggots, on the other hand, were a savory delicacy. He was more than content to let someone else take care of actually slaying the avian creatures.

To his relief, the pond water was more than satisfactory for his purposes today, both in temperature and in general viscosity. The air around Fred was cool and dry, which was pleasant since he was sensitive to temperatures for a few hours after waking up. Cool was better than hot.

Fred preferred cold water to remove the insect remains from his claws. His limbs were still quite agile for his advanced age, but it was to his advantage to keep his grasping appendages free of obstruction.

Mud was also quite useful as a soothing lotion for sore paws. An opossum that tended to his body parts tended to live longer, which was Fred’s constant goal.

It smelled like the hogs hadn’t been near the pond for a while. Fred’s pink nose on his long, thin snout couldn’t detect even a whiff of hog excrement, just overly ripened corn from the fields, a promising scent. There would be plenty of tasty, sated insects in the cornfields for dessert later.

The dark, deep pond — frequented by the farm animals but ignored by the human creatures — was hidden behind the three-story wooden barn, itself shabby with weathered planks that had been painted red in more prosperous times, now missing the occasional slab. The current humans weren’t concerned with appearances.

Fred found the structure imposing, if only in size. These human creatures were generally clueless about important things, but they did construct impressive objects for habitation, both for themselves and for their animals.

The increasing chill in the air meant that it was probably getting close to sundown. The sunlight was getting dimmer, which annoyed Fred somewhat.

There were no clouds, and he hoped that it wouldn’t rain. It wasn’t that he disliked rain. His thick, gray fur protected him from hypothermia, and he quite enjoyed shaking and shimmying to get the heavy raindrops off his bristly hairs.

However, Fred missed the light that clouds restricted. It was bad enough that the light receded every day, even though that made life safer for opossums. In the few hours Fred was awake during the day, he loved to watch the joyous play of sunbeams on plants and ponds, making their colors dance, a pleasure possibly unique to this planet.

Fred might be elderly, but he was certain that his body and mind were in excellent shape, if only because he kept both active.

There was still time before supper, and so Fred decided to slip into the pond for a quick, relaxing swim. He liked to feel supported by the water while he paddled around and opened his mind to discussions with the microbes who lived in the pond, probably his best friends on the farm.

As the ticks in his fur fell off and floated away, Fred swallowed each one with gusto. Crunchy ticks soaked in fragrant pond water made for a delightful appetizer.

Fred deliberately thought of nothing as he concentrated on soaking up impressions from the microbes in the pond. In structure, they were simpler creatures who, however, when united, far outmatched more complex creatures in powers of observation and analysis. He could only hope that he didn’t bore them with his thoughts.

The communication chain worked best top to bottom. More complicated creatures could send messages down to creatures with less complicated structures fairly easily. The less complicated creatures had no trouble taking these messages apart and analyzing them.

However, it demanded strenuous concentration for a creature with a more complicated structure to understand what the less complicated creatures were communicating. Their messages came slowly and were often interrupted. Fred had the patience and physical vigor necessary for listening. Plus, he enjoyed hearing from the microbes.

Most opossums ridiculed him for talking to the microbes. Fred got tired of explaining that he listened far more than he talked and that opossums were foolish to ignore sources of information.

Other opossums were just as receptive as Fred by nature, but they preferred to spend their time eating, mating, and sleeping.

Today, floating in the pond, Fred engaged in pleasant chitchat with the microbes, nothing serious, just comments on life in general. While listening to them, he thought he sensed something else, something not quite right in the universe, but nothing he could put his paw on. The microbes themselves had no worries they wanted to pass on.

After splashing around for many enjoyable minutes, Fred decided it was time to think about setting his refreshed legs in motion and joining the semi-feral farm cats for supper.

The felines did consume the occasional small rodent on the farm but also let themselves be fed outside the farmhouse by the somewhat capricious though kindly human creatures.

Fred and the cats got along well enough. It was only when a new cat arrived that Fred had to re-establish the pecking order ─ or, in this case, the order of growling, pawing, and slapping ─ for the feral but currently resident mammals on this farm.

Cats had to be reminded that opossums ruled. He had managed to acquire their respect one by one as they showed up at the farm.

For some reason feline tourism abounded in this area. Fickle cats always thought they might get better food at a different farm.

They were wrong. The occupants of this dilapidated farmhouse were quite skillful cooks. The repast they set out for visiting animals was always delicious; it just tended to arrive at varying times. Fred had long since learned to be flexible in his eating habits.

However, it was common knowledge, or perhaps inherited memories, that opossums shouldn’t go near humans, if only to avoid becoming a premature component of the food chain. Some humans were known to consume opossums, calling them tasty vittles.

The humans in this house didn’t use that kind of language, but a cautious opossum took nothing for granted.

Caution had its benefits, one of which was avoiding the necessity of “playing possum.” It was beneath Fred’s dignity to lie immobile, roll his eyes, draw back his lips, bare his teeth, and expel noxiously fumed secretions from his anal glands. It took far too many swims in the duck pond to rid himself of that stench afterwards.

Fred developed the habit of waiting for darkness before he approached the farmhouse to partake of the banquet the humans would offer. He always only ate after the humans returned inside.

It was getting darker, and so Fred swam toward the edge of the pond. Out of habit, he perked up his dark, rounded ears, not to listen to the motors of the tractors, combines, and harvesters on the farm, but to be open for any important information.

Opossums had a special talent for hearing, for listening to the grunts and lowing of farm animals, of course, but also for absorbing messages from other more complicated structures in the universe.

Most such data was boring, but every now and then Fred picked up on something useful. Way back when, his ancient ancestors had detected the behavior of an approaching asteroid and made arrangements to survive underground.

Unfortunately, it wasn’t possible to warn the dinosaurs. They just didn’t listen to the pleas of primitive, tiny mammals. This was still the case today. Opossums couldn’t communicate with more complexly structured creatures because such creatures couldn’t concentrate on what the opossums said.

Right now, Fred could only be certain that he sensed powerful, individual thoughts from the six-legged creatures he intended to devour later. Flies, mosquitoes, and gnats, buzzing and humming contentedly, were busy selecting their own sources of nourishment in the cornfields.

Fred stomped out of the pond and shook the water off his fur. Feeling energetic again, he scampered around the barn and down the hill to the two-story, old-fashioned farmhouse, probably painted white some time ago but now displaying graying boards.

His timing, as always, was perfect. The screen door opened and a tall, female human, followed by her loquacious, diminutive offspring, brought out bowls of meat and milk and water. Today, as so often, the child seemed to understand the greetings Fred sent him.

When the adult headed back into the house, Fred jumped up the steps to the porch where the door to the kitchen was. Fred growled and then shoved his way through the crowd of cats, who submissively moved aside and made a path for him.

“Fred’s here,” the child shouted. Since the creature wasn’t even half the size of his parent, and since Fred only received benevolent telepathic thoughts from him, Fred wasn’t afraid of him, though Fred did feel more secure when the all the humans went back into the house.

Fred, of course, did have a distinguished opossum name, but after the child had started yelling “Fred” at him in such a delighted tone of voice a few years ago, Fred decided to claim it for himself. The name “Fred” brought about pleasant associations with the evening meal the humans provided.

However, survival instincts demanded that Fred wolf down the food and drink and then head for the cornfields before the humans could suddenly pose any threat. While his behavior might be considered rude, he consoled himself with the thought that the humans could always talk to the feral cats if they needed mindless repartee with their outdoor dinner guests.

Fred scurried over to the nearest cornfield, running until he was convinced that he was invisible to the humans. As expected, he found sufficient insects for his dessert crawling around between the muddy rows.

When he couldn’t eat any more of the tasty, crisp insects, Fred lay down between a few stalks of corn and looked up at the sky. This was the time of day when he was most awake.

Without the food the humans provided, he would have to be off hunting. However, with a temporarily full stomach, Fred could tend to what he liked best. As soon as the humans extinguished the toys in their house that lit it up, the cloudless sky gave Fred an excellent view of outer space.

He ceased all conscious thought, opened his mind to any impressions he might absorb, and concentrated on the stars.

Fred always loved those points of light, the hints of color in the black night. Fortunately, the air was dry and cloudless. He had a completely unobstructed view, which should have made him unreservedly happy, but he sensed something was wrong.

It took a while before he could comprehend the messages. He directed his full concentration upwards. The stars didn’t radiate their usual joyful contentment. A sense of apprehension pervaded, which was unusual for the stars and galaxies that generally moved with the abandon that the laws of physics allowed.

Although it was his habit to spend about an hour in the cornfields enjoying his dessert, this time Fred spent the entire night watching and listening. It took that long to make sense out of the feelings he was absorbing, to translate feelings into concrete thoughts.

There were just so many stars to listen to. Eventually he understood that they were all broadcasting the same message, however with varying details.

The universe was in danger because one of the infinite numbers of parallel universes was on its way to collide with this one. Since the parallel universe was larger, after the collision, the parallel universe would dominate the resulting, newly formed, compound universe.

The physical laws of the parallel universe were such that matter would be unable to form, and existing matter would quickly degenerate to pure radiation.

This prospect made the stars sad, which Fred the opossum could understand. Being an opossum on this farm on this planet occasionally had some disadvantages, but he had no desire to be turned into an unstable collection of meandering photons.

More to the point, however, how could this collision be prevented?

Fred knew when he needed to brainstorm. Whenever he was at a complete loss, he consulted the microbes in the duck pond. They always listened to him. Each individual microbe didn’t know much, but when they joined to a telepathic group mind, they often came up with excellent ideas.

Fred shuffled out of the muddy cornfield and, as soon as he was on firm ground, scurried over to the duck pond and dived in.

“Yo, microbes,” Fred began his telepathic message. “Listen up. We all have a problem.”

“One of the new cats steal your food again?” the microbe group mind asked.

“No, no,” Fred said patiently. “This is a real problem, unless you like the thought of losing your physical existence and being turned into pure energy.”

That got their attention. Fred explained that some stars at the outer edge of where dark energy pushed them had noticed disturbing changes.

Comparing observations, the shrewd quark stars came to the unanimous conclusion that a parallel brane of a universe was approaching the brane of this one. Collision was probable. The approaching universe was larger and would absorb this one, converting all matter here to radiation.

Fred sensed the uneasiness and uncertainty that this caused among the microbes.

“Any ideas on how we can prevent this?” Fred asked.

“Obviously this is more than microbes can manage,” the microbe group mind answered. “Tell your humans to build something or do something. They’re good at that kind of thing.”

“You know that they don’t have the patience to listen to me,” Fred said. “On their own, they won’t notice anything until it is too late. Then their building skills won’t help them.”

“Still, microbes don’t move universes,” the microbes said. “Maybe we should just go with the flow. Eventually this universe will peter out into nothing anyway. Why not be part of a radiant road show first?”

“Eventually is a long, long time,” Fred said patiently. “Think about it. You enjoy your one-celled existence, absorbing, expelling, moving about. You sense pleasure from the physical feeling when chemicals or life forms move through your membranes. I can’t imagine anything more boring than floating around in a cloud of nothing.”

“Hmm,” the group mind said. “Maybe you’re right, but we still aren’t capable of doing anything.”

“We have to come up with some idea,” Fred said. “Or else we lose it all. You microbes always have a solution to things. Find one for this problem.”

“We can’t do anything, but we might be able to function as intermediaries,” the microbes said after a long pause. “We’ll pass your news down to the molecules, they can pass it down to the atoms, and they can pass it down to the subatomic particles. We’re all forms of matter and, like you said, all have something to lose.”

“Excellent,” Fred said. “I could probably pass the message down as far as the subatomic particles myself, but I wouldn’t be able to hear their replies or suggestions. Just concentrating enough to listen to you takes a lot out of me.”

“Right,” the microbes said. “Each level of complexity can only easily understand communications from a maximum of one lower level. If we concentrate, we can hear the answers from the molecules, they can hear the answers from the atoms, and so forth. Eventually your message would have to reach dark matter and dark energy.”

“Perfect,” Fred said. “I’m sorry I have to involve you, but no one listens to the stars except me.”

“Don’t get your hopes up, though,” the microbes said. “There is a definite problem that the message could get garbled at every level or that it will turn out that no one can do anything.”

“Try anyway,” Fred said. “I have every confidence in you.” This wasn’t completely true. Fred knew that the microbes’ group mind had a capacity for thinking that was far beyond his. Unfortunately, microbes also had difficulties in staying with one project. They were spontaneous, more than a little flighty, and got bored easily.

He had no idea what to expect from subatomic particles all the way down to dark energy. Even if there was a general willingness to do something, Fred had no idea what could be done.

He could only rely on the microbes to initiate some action.

Actually, the sun was now fairly high in the sky, and Fred needed to find a safe place to nap. To get to the next little wooded area Fred would have to retrace his steps past the farmhouse. This seemed too risky. The child was already playing in the front yard. Fred could run fast, but possibly not fast enough.

There were a few thorn bushes at the back of the ramshackle barn. It would be uncomfortable for Fred to crawl between the barn and the bushes, but the location was unlikely to attract the attention of the human creatures. So, no choice.

“I’ll be back later,” Fred said to the microbes as he crawled out of the pond and walked reluctantly over to the bushes. Once he was between them and the barn, he felt invisible enough to sleep for a few hours.

Listening to the microbes and thinking about the fate of the universe must have tired Fred more than he thought. When he woke up, it was very dark, and he was hungry. He suspected that the cats had already consumed his portion of the supper banquet that the humans put out. He would have to survive on whatever he could forage.

First, though, there were more important things to take care of. He wanted to know what the microbes had accomplished, if anything.

He stumbled over to the duck pond and dived in. When he was physically surrounded by the microbes, it was less strenuous to listen to them.

“Yo, Fred,” the microbes broadcast into his consciousness.

“Yo, microbes,” Fred answered. “Do you have any news?”

“Yes and no,” the microbes answered. “We’ve been passing the news back and forth all day. We got answers and questions and then answers and more questions and then more answers. For the longest time, the only answer was that there was nothing that could be done. We’re completely worn out.”

“Thanks for trying,” Fred said. “I know this was hard work for you, always concentrating on messages from lower levels of structure. No wonder you’re exhausted.”

“We would have given up hours ago,” the microbes admitted. “But we didn’t want to disappoint you. You’re a good friend, Fred.”

“Thanks, but what is the current situation?” Fred asked.

“The short version is that it’s unanimous through the structures all the way down to dark matter. No one wants to let a parallel universe obliterate this one,” the microbes said. “Dark energy is still undecided.”

“Why?” Fred asked.

“Who knows?” the microbes said. “We’re awfully tired.”

“I know,” Fred said. “If the universe survives, it will be exclusively due to your hard work. The whole universe will owe its existence to you.”

“Yeah, well,” the microbes began. “Only if we succeed, and we are getting too tired to do anything more.”

“I know,” Fred said. “But could you make one more attempt? How about if you send down the thought that dark energy won’t have anything to do in the new universe. A universe consisting solely of radiation doesn’t expand. Any kind of energy would find itself paralyzed.”

“We’ll give it one more try,” the microbes said. Fred heard how fatigued they were. He hoped he wasn’t asking too much. He didn’t want to threaten their existence, especially if the whole attempt turned out to be in vain.

He waited and floated in the pond. He was starving, but it didn’t seem right to abandon the microbes after all they were doing.

“Success,” came the tired reply from the microbes. “Dark energy understood your thought that it had as much to lose as the rest of us. At this moment, it is calculating how it needs to steer the brane this universe is in away from the approaching one. It thinks it is doable. Dark energy just has to pulsate the rate of expansion instead of constantly increasing it. That should yank the universe out of danger.”

“Great,” Fred barked. “You really went to your physical limits and saved us all! How can I make it up to you?”

“To be honest,” the microbe group mind said. “We need reinforcements, additional, energetic microbes to support the group. Can you help us with that?”

Fred’s first thought was to sacrifice a few cats, but he quickly abandoned that suicidal prospect. If he attacked one cat, the others would make cat food out of him.

At that moment, a few ducks landed on the water. Ducks! The proverbial solution of killing two birds with one stone. Fred could attack some ducks and then dunk their cadavers into the pond for the microbes. Once sufficient microbes made their way out of the ducks, Fred could slaughter one duck for his own, long-delayed, evening meal.

Fred was tired as he quietly swam over to the first duck, tired but determined enough to swing a mighty paw and whack his first prey with his claws. It was no problem to then hold the creature under water for a sufficient length of time. The microbes deserved no less for saving the universe. Fred would eat later.

* * *

Originally published in Pulphouse, Issue 18

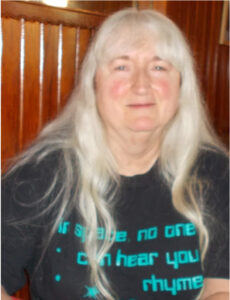

About the Author

About the Author

Mary Jo Rabe grew up on a farm in eastern Iowa, got degrees from Michigan State University (German and math) and University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee (library science). She worked in the library of the chancery office of the Archdiocese of Freiburg, Germany for 41 years, and lives with her husband in Titisee-Neustadt, Germany. She has published “Blue Sunset,” inspired by Spoon River Anthology and The Martian Chronicles, electronically and has had stories published in Fiction River, Pulphouse, Penumbric Speculative Fiction, Alien Dimensions, 4 Star Stories, Fabula Argentea, Crunchy with Chocolate, The Lorelei Signal, The Lost Librarian’s Grave, Draw Down the Moon, Dark Horses, Wyldblood Magazine, and other magazines and anthologies. You can find her blog at: https://maryjorabe.wordpress.com/